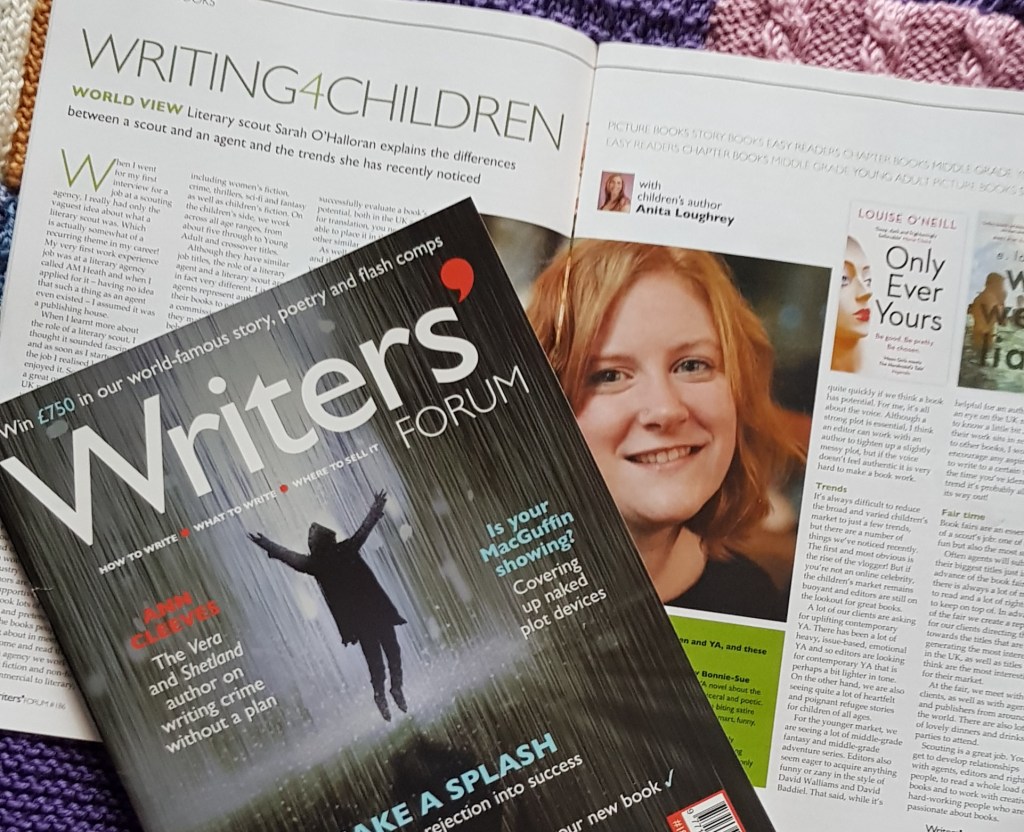

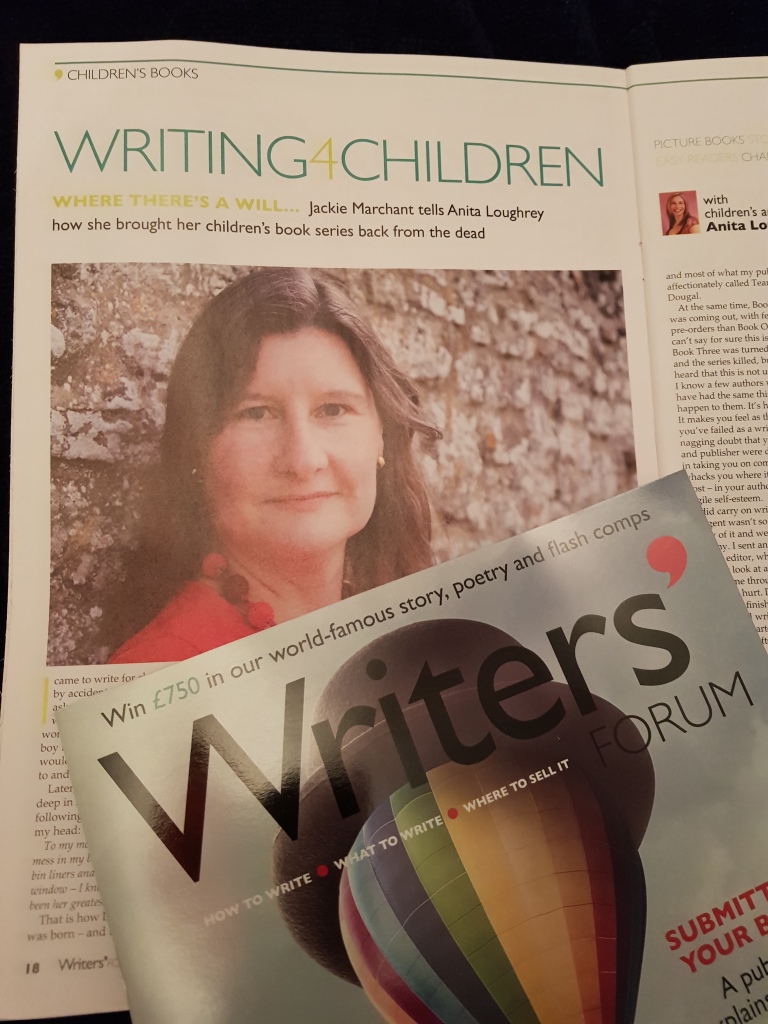

In the March 2018 issue of Writers’ Forum, I interviewed Jackie Marchant about her Dougal Daley series and how it was revived from the dead. Jackie told me her inspiring story of how the books were given an incredible face lift by changing the name of the main character and using a new illustrator, after meeting Louise Jordan at the London Book Fair.

Jackie explained the idea to write for children came by accident, after her son asked a question about writing a will, which left her wondering – why would a boy need to write a will? Who would he leave his possessions to and why? Later, while standing knee deep in his messy bedroom, the following words popped into Jackie’s head – To my mother I leave the mess in my bedroom, to put into bin liners and throw out of the window – I know that has always been her greatest wish. That is how Dougal Daley was born – and those words are in the first book.

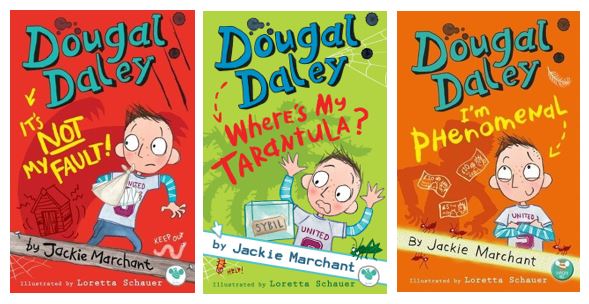

Her idea and first draft got her an agent and a two-book deal with a major publisher. This was all hugely exciting. The original Dougal did not have the surname Daley. He was called Dougal Trump. The author on the cover was D. Trump. Her first published book was called I’m Dougal Trump – it’s NOT my Fault! This was before a certain other D. Trump became quite so well known.

“I was unsure about doing school visits and my publisher thought it would be a great idea to make out that Dougal was the author of the books himself. His name would go on the cover rather than mine, but I wouldn’t have to face the angst of standing before a bunch of kids to explain myself (honestly couldn’t think of anything more terrifying). So, the series was launched and all was well.”

Jackie Marchant

Then disaster struck. She lost my wonderful editor, who went freelance, her editor’s boss, who loved Dougal, her publicist, the marketing person and most of ‘team Dougal.’ At the same time, Book Two was coming out, with fewer pre-orders than Book One and Book Three was turned down.

“I can’t say for sure this is why Book Three was turned down and the series killed, but I have heard that this is not unusual. And I know a few authors who have had the same thing happen to them. It’s horrible. It makes you feel as though you’ve failed as a writer. That nagging doubt that your agent and publisher were deluded in taking you on comes and whacks you where it hurts most – in your author’s already fragile self-esteem.”

Jackie Marchant

Jackie revealed to me she felt like a failure. Then she went to the London Book Fair. That is where she stumbled across Wacky Bee Books. After talking to Louise Jordan, founder and owner of Wacky Bee, Louise ordered the first book of the Dougal Trump series online. A few days later, she contacted Jackie to say she loved it and would like to publish all three books with new titles.

“Things are looking up and I feel like a proper author again. I hope my perseverance inspires others not to give up hope.”

Jackie Marchant

You can read a review of Jackie Marchant’s third book in this series, Dougal Daley II’m Phonomenal, on my blog here.

Find out more about Jackie Marchant and the Dougal Daley books on her website: www.jackiemarchant.com and on Twitter: @JMarchantAuthor

You can read the complete interview in the #197 March 2018 issue of Writers Forum.