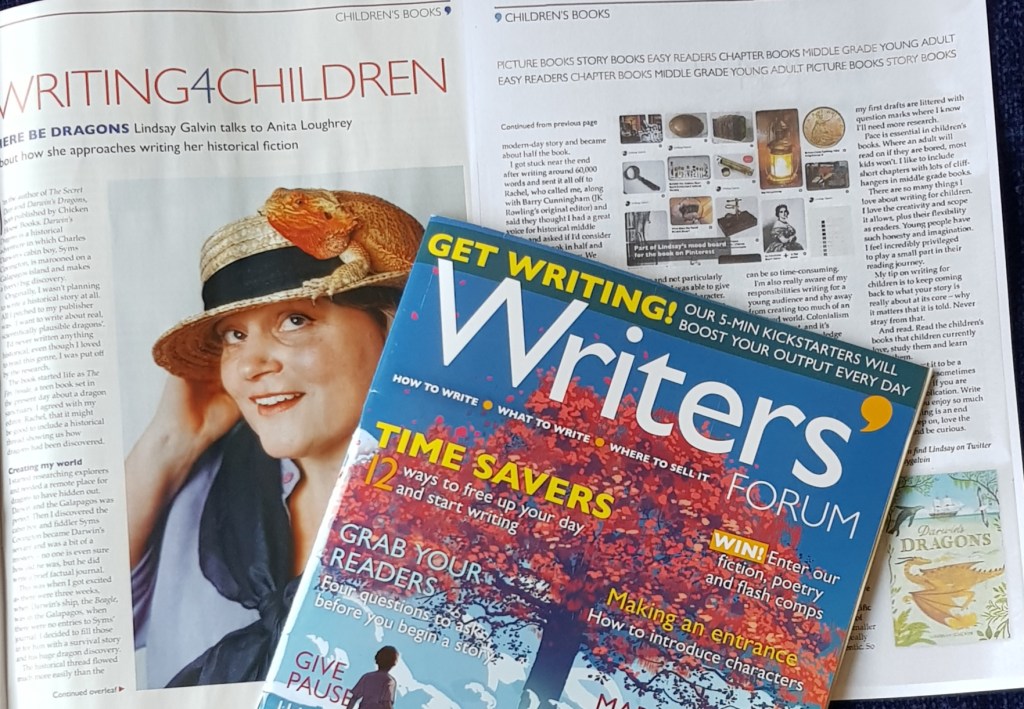

For my Research Secrets slot in this month’s issue of Writers’ Forum #253 19 Apr 2023, Barbara Henderson explained to me some of the research she did into the building of the Forth Bridge to Dunfermline for her middle-grade novel, Rivet Boy

Rivet Boy is her eighth book for children and was published by Cranachan Publishing on 16th February 2023. It features Edinburgh, Dunfermline and the Firth of Forth as key settings and is woven from historical events entwinned with her imagination.

As a historical fiction writer, Barbara is always on the lookout for story possibilities. Almost every single one of her books was inspired by reading an interesting snippet or visiting a heritage site. She told me she has been fascinated by the Forth Bridge for a long time. Her first job was across the Forth. She had to cross the water daily, which meant either rattling across the iconic Forth Rail Bridge by train or staring at it in awe as she drove across the road bridge beside it. In fact, her wedding reception was held right beneath the bridge. She said it eventually clicked – the world was crying out for a light-touch engineering book about the building of the Forth Bridge as readers love knowing a story is rooted in real events.

Barbara’s tip to other writers wanting to write a novel on true events is to read around the topic for a few months to gain an overview. Once a possible story presents itself, find the person who knows most about it. They will love being asked about it – all their friends and relatives will already be thoroughly sick of hearing about their pet interest and your keen interest will be very welcome.

Barbara explained for her children’s book, she needed a child character to take centre stage. So she researched the ordinary people who built this bridge and discovered a book called The Briggers – The Story of the Men who Built the Forth Bridge. However she found many of the anecdotes in this book of young people were depressing, and the Briggers had campaigned long for memorials to all the men who died during the bridge’s construction. The youngest victim she found was David Clark, a 13-year-old who fell and also a young boy called John Nicol who fell into the water from the bridge and survived unhurt, who became her main character.

Barbara hunted down the author, Elspeth Wills and found she was part of a research consortium of local enthusiasts who also called themselves ‘The Briggers’. More online digging even yielded an email address. Frank Hay answered her email and agreed to talk on Zoom. Barbara revealed her most valuable resource turned out to be Frank, and the others who had already studied the subject: ‘The Briggers’. When she asked for more information about John, the boy who survived, Frank spent a few days to look into it for her and sent her a ten-page document: He’d checked the census records, identified the most likely John Nicol, found his birth certificate, his parents’ marriage certificate and his two addresses in Dunfermline.

In addition, he discovered his father had been killed in an industrial accident in Australia before John was born. For a time, the widow was supported by charity, but it made sense for John to seek work when he was twelve, old enough to be a breadwinner. The newspaper extract describing John’s accident was also in there. Barbara was able to use this information to construct a timeline.

“I tend to think of historical fiction as a washing line. Your fixed events and real people are the pegs, pinning the story to the timeline. These are the things that are both true, incontrovertible and relevant to your story. In between, the washing can flutter in the wind of your imagination.”

Barbara Henderson

Construction was big for this particular book, so Barbara had to research the processes. She explained she finds it astounding that these Victorian engineers managed to calculate so accurately without the aid of modern computer technology. Much of the foundation work had to be conducted beneath the water. By the time her main character John begins his work on the bridge, the structure had emerged from the waves, but the fact that she feature so many details and incidents from real life meant that she had to constantly double and triple check that she had my order right.

In an early draft, she had the squirrel Rusty visit John on the bridge from North Queensferry – only to realise that it couldn’t have happened yet because the cantilevers weren’t connected at that point. Her tip is also not to assume anything. When describing the noise of the building site, she referred to a list along the lines of ‘hammering, drilling, scraping and shouting’ – only to be informed all drilling was done in the workshops, some way off and in advance. Many sounds added to the cacophony on the site, but drilling was not one of them.

Research can be a lonely business, as can writing. Her final tip is to join a writing group with similar interests to you. Barbara is part of the Time Tunnellers, a group of five historical fiction writers for children with weekly YouTube videos and blogs aimed at schools and historical fiction readers. Barbara told me she often learns something new from unexpected places – including my fellow Time Tunnellers’ posts.

You can discover more about Barbara Henderson and her books by following her on her website: www.barbarahenderson.co.uk, and follow her on Twitter @scattyscribbler and Instagram @scattyscribbler and @BarbaraHendersonWriter on Facebook.

To read the complete feature you can purchase a back copy of the #253 19 Apr 2023 issue of Writers’ Forum by ordering online from Select Magazines.

To read my future Research Secrets or Writing 4 Children interviews you can invest in a subscription from the Writers’ Forum website, or download Writers’ Forum to your iOS or Android device.