For the last ever issue of Writers’ Forum #254 May 2023 I interviewed Liz Flanagan about her inspiration and worldbuilding for the Wildsmith adventure series.

Liz explained the spark for the Wildsmith stories occurred in the strange quiet summer of 2020 when life was so starkly different from what we’d expected. Before her daily walk of those lockdown months, Liz had never realised how essential walking in the woods was for her mental health.

“Even in those dark and worrying times, as soon as I was outside under the trees, I started to feel better, and I’d return from my walk more able to cope.”

Liz Flanagan

She found writing was an anchor for her and tried new things to keep busy when her other work was cancelled. She discovered she enjoyed writing for younger children. Her agent, Philippa Perry, suggested writing a middle-grade series, full of magic and hope. It’s not a massive leap to see where Liz got the idea for a beautiful forest, fostering magical animals, and discovering the magical power to heal animals and speak to them.

Liz elaborated she had been fostering cats and kittens for an animal charity, and so had three unexpected additions to their household during lockdown – a very nervous young cat and her two kittens. She often wished she could speak to her foster animals to reassure them and to find out what was wrong when they were ill or scared.

She told me she believes fantasy lets us explore real-world problems in an oblique way that can be safe for young children. Perhaps all writers do this: taking the stuff of our lives and weaving it into stories, even if it’s not immediately apparent where each element came from?

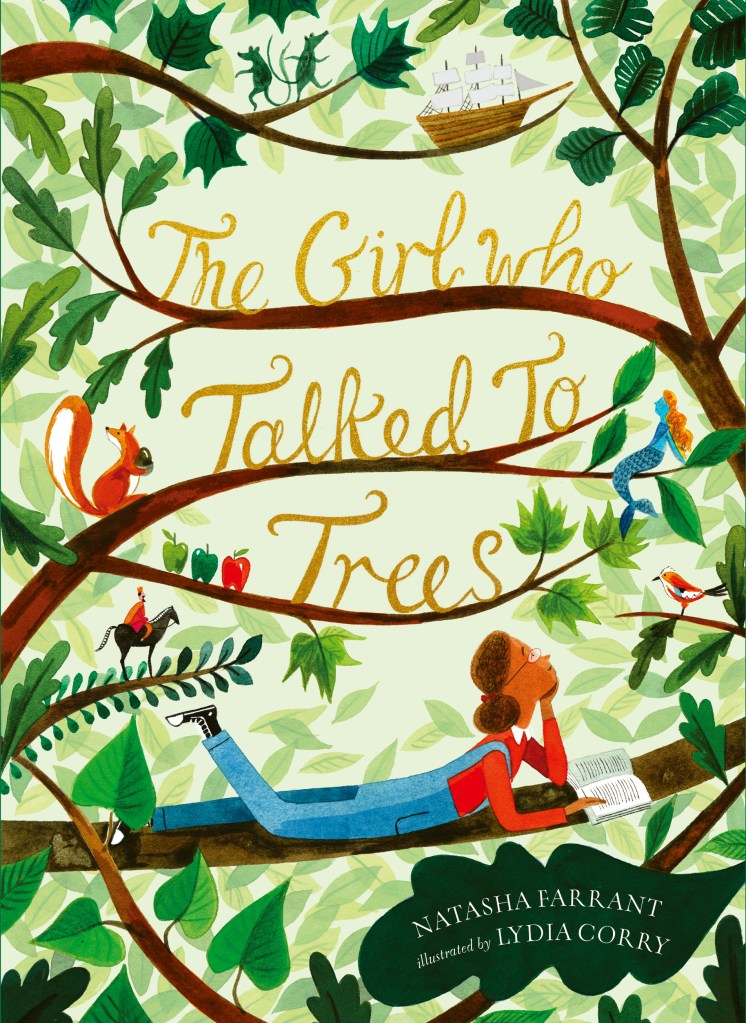

Liz said she started sketching out ideas on a piece of paper – characters, issues, locations – and this grew into a detailed chapter by chapter outline. Her outlines tend to be about a quarter of my final word count as she thinks it is think easier to make changes to a plan than it is to rewrite a whole story. She created a map, and added to it as the series grew. She also did sketches of rooms and locations around Grandpa’s house to make sure it made sense on the page. Joe Todd-Stanton’s bought these places brought to life with his incredible art.

In terms of worldbuilding she needed to be clear on the magical attributes of her characters from the start. she explained it had to be consistent within the story world and also have limits – otherwise there’s no tension. But, the witches’ spells and the wildsmith’s magical healing were described in more detail quite late on in the writing process.

After writing the first two books Liz realised the passage of time was important. and decided that time passing at the rate of around one season per book should be a feature, which is highlighted on the covers. Book one has glorious green summery forest leaves, and book two has lovely autumnal shades.

The story developed with a longer-term conflict in the shape of the war, which begins in book one and is resolved by book four. Then each story has an individual problem to solve, connected with rescuing a particular magical creature (or being rescued by one in the case of book three). There are several baddies who re-appear, as well as friends whom Rowan isn’t sure she can trust.

Liz revealed it was a challenge to keep the conflict mainly happening ‘off-stage’ so it remained age-appropriate and not too scary, but early reviews from teachers have been really encouraging. Having short chapters helps to keep the children turning the pages. It gives you that structure and encourages a natural ‘cliff-hanger’.

“My protagonist needed to have a very clear goal throughout, even if this changes as the story develops. I’m used to having lots of action in my older books, so I wanted to make these younger books equally exciting. However, it was certainly a challenge for me, learning how to write simply while keeping the pace, learning what to leave out and what to keep in.”

LIz Flanagan

LIz’s writing tip for writing for children is to think back to your own childhood. She said one thing we know really well is the childhood we experienced and how we ourselves felt as a child of different ages. So we have this incredible resource, if we can access these memories.

“Having once been a bookish, animal-fixated child who loved to climb trees, I definitely think I wrote Wildsmith: Into the Dark Forest for the seven-year-old I once was.”

Liz Flanagan

And even if we can’t retrieve our own memories, we can observe the children around us. Liz found this a helpful place to start: instead of trying to please everyone, select a child you know, or the child you once were, and write to please them.

Liz Flanagan can be found at: https://lizflanagan.co.uk, Twitter @lizziebooks, Instagram @lizziebooks17

To read the complete feature you can purchase a copy of #254 May 2023 issue of Writers’ Forum by ordering online from Select Magazines.

To read my future Writing 4 Children or Research Secrets interviews you can invest in a subscription from the Writers’ Forum website, or download Writers’ Forum to your iOS or Android device.