In the latest issue of Writers’ forum I talk to Sophie Kirtley about how she created the fictional worlds in her debut novel, The Wild Way Home, which came out with Bloomsbury in July 2020.

The Wild Way Home tells the story of two very different children: Charlie, who is from our time, and Harby, a boy from the Stone Age. It’s a story of friendship, courage and adventure as Charlie and Harby journey together through the wild green Stone Age forest in search of Harby’s missing baby sister. You can read my review of this mid-grade novel here.

Sophie told me The Wild Way Home was inspired by her own childhood. When she was little she often played with her friends in a wood near where she lived; it was called Mount Sandel Forest. She vividly remembers the feeling of the place – its sense of mystery and seclusion… and wild freedom. Only years later did she realise that in this very forest archaeologists had found the remains of a Stone Age settlement, it was in fact the oldest human settlement in all of Ireland.

The idea that she’d played somewhere where children had been playing for millennia was the spark which ignited this story; it made her curious about the Mesolithic children who’d played in that forest so many years before she had. She started to imagine what might’ve happened if she’d actually met one of those Stone Age children and that’s how the story-spark ignited and the story-flames raged to become, eventually, The Wild Way Home.

Sophie told me creating a fictional world can be a bit of an overwhelming ask. She explained she works her way outwards from very small details towards creating a bigger picture or building a world. She love interesting objects or strange place names or curious graffiti or fascinating gravestones.

Once something small like this has caught her eye, she let herself interrogate it; asking lots of questions about the possibilities that the small-strange-something might have thrown into her mind.

“Little by little I build all these little details together into something bigger, kind of like creating a story patchwork. In The Wild Way Home I did this with Stone Age small things that fascinated me – artefacts from museums or from ancient sites.

The intricacies of the time-slip elements of The Wild Way Home took a lot of work in order to make the shift in time smooth and believable. The setting of the story really helped me; when Charlie ends up in the Stone Age a lot of the natural features in the landscape remain the same – the river, the cave, the cliff – these physical links plus having Charlie’s consistent narrative perspective helped to carry the story between worlds.”

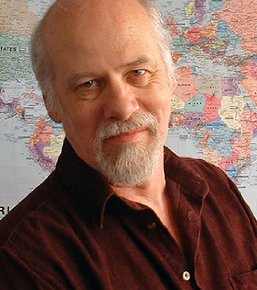

Sophie Kirtley

Sophie revealed writing a book set in a specific period can be tricky. You’ll feel the weight of responsibility to ‘get it right’. She did oodles of reading and researching about pre-historic life, but even within that different sources can offer contradictory angles and Sophie is adamant that you should not to tie yourself in knots with the pressures of absolute accuracy.

“At the end of the day, this is fiction, and we’re writers aren’t we? And we’re definitely allowed to make stuff up. Well that’s what I told myself anyway as I picked through my research, magpie-like, choosing what I found fascinating and eschewing the less fun bits.”

Sophie Kirtley

Sophie explained when you’re writing for children anything really is possible. Children are accepting of adventures in a way that adults aren’t – it’s very liberating as an author. Child readers are also incredibly judicious and deserve the best – they’re a hard audience too, because if they’re not gripped they simply won’t read on. Just like they simply won’t eat peas or cheese or whatever the foible may be. Sophie loves the challenge of writing for children – delivering them something they like the taste of.

If you want to write for children then there are two main pieces of advice Sophie offered: Read and listen. Read as many contemporary children’s books as you can and read them as a writer, learning along the way. Also listen to kids you know, how they talk, what makes them laugh, what makes them grump… or even think back to you as a child and squeeze your big feet back into those small shoes.

And one final thing, writing is always going to have its ups and downs, its good days and bad days. Just keep writing and don’t give up.

You can discover more about Sophie Kirtley on her website: www.sophiekirtley.com and follow her on Twitter @KirtleySophie.

To read the complete feature you can purchase a copy of #230 Mar2021 Writers’ Forum by ordering online from Select Magazines.

To read my future Writing 4 Children or Research Secrets interviews you can invest in a subscription from the Writers’ Forum website, or download Writers’ Forum to your iOS or Android device.