In November 2017, I interviewed librarian Joy Court, about some of the children’s book awards she was involved with for my Writing 4 Children slot in Writers’ Forum. Joy is a professional librarian and was the Chair of the CILIP Carnegie and Kate Greenaway Medals – the oldest and most prestigious children’s book awards in the world of children’s literature.

The Carnegie Medal

The Carnegie Medal was introduced by the Library Association 80 years ago and is awarded for outstanding writing for children and young people. It is named after Andrew Carnegie, a self-made industrialist who made his fortune in steel in the USA. His experience of using a library as a child led him to resolve:

‘…if ever wealth came to me it should be used to establish free libraries.’

Andrew Carnegie

He set up more than 2800 libraries across the English speaking world and, by the time of his death, over half the library authorities in the UK had Carnegie libraries. He must be turning in his grave with the current shocking spate of library closures.

One misconception of the Carnegie Medal is that it has been taken over by teenage and YA publishing. There is only one definition of a children’s book – it is published on a children’s list (technically listed on the Neilsen database). Until the industry differentiates between children and teenage publishing we cannot.

A book can be great for many different reasons. For the purposes of the Carnegie we are looking for a book of outstanding literary quality.

“The whole work should provide pleasure, not merely from the surface enjoyment of a good read, but also the deeper subconscious satisfaction of having gone through a vicarious, but at the time of reading, a real experience that is retained afterwards.”

Past winners include: Tanya Landman with Buffalo Soldier, published by Walker Books; Sarah Crossan with One, published by Bloomsbury and 2017’s winner was Ruta Sepetys with Salt to the Sea, published by Puffin.

The Kate Greenaway Medal

The Kate Greenaway Medal was created 60 years ago to award outstanding illustration for children and young people and was named after one of our most iconic British illustrators.

Previous winners include: William Grill with Shackleton’s Journey, published by Flying Eye Books; Chris Riddell with The Sleeper and the Spindle, published by Bloomsbury and 2017’s winner was Lane Smith with There is a Tribe of Kids, published by Two Hoots.

Judging

Both medals are unique as they are judged by librarians and are completely devoid of any commercial influence. Neither publishers, nor authors can submit their books and the judging is not influenced in any way by sales or publicity. She read every single book nominated for them but does not get to vote. Joy’s job was to ensure every book got a fair chance and all the procedures were followed correctly.

In the early days, judging was carried out by men in suits behind closed doors (the Library Association Council). Now the judging process is under the control of children’s librarians from the 12 regions of the UK including Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. They are elected for a two-year-term by their regional Youth Libraries Group committee, thanks to the pioneering work of Eileen Colwell, the first specialist children’s librarian and founder of the Youth Libraries Group. She must also be turning in her grave at the loss of specialist posts.

Gradually the system of nominations, election of judges and the criteria has been honed and improved to keep pace with new developments in the world of children’s publishing. You have to be a member of CILIP to be able to nominate and can then nominate two books for each award. Unlike many other awards we publish our judging criteria on our website.

2017 winners

Impact

These awards have a huge impact on the world of children’s literature because of the enormous shadowing scheme. There are around 5000 groups shadowing the awards each year, with hundreds of thousands of young readers reading and commenting on the shortlisted books. This means a lot of shortlisted books will be sold and figures show an ongoing increase in sales from winning the medal.

The medals have always been international in outlook. Books first published elsewhere in the world can be eligible providing they are published in the UK within 3 calendar months of original publication. In 2014, books in translation (first English translation published in the UK) became eligible. We can genuinely say that the medal awards the best writing in the world.

You only have to look at the list of winners to see they have become classic titles that are always available in bookshops. I believe 80 years of ‘they all want to win the medal’ has led to the development of the UK ‘world-beating’ publishing industry we have today.

UK Literary Association Book Award

Joy is also a Trustee and National Council member of UKLA and helps to manage their book awards. They are nicknamed the ‘Teacher’s Carnegie’ as they are the only awards judged by teachers. The 60 teacher judges involved in the initial shortlisting are selected from around the geographical area where the next UKLA international conference will be held – 2018 is Cardiff.

UKLA invite publisher submissions according to three age categories 3-6, 7-11 and 12-16. A publisher can submit 3 books per imprint. A publisher like Penguin Random House has many imprints: Jonathan Cape, Bodley Head, Corgi, Puffin, Red Fox, etc.

In 2017, the winning book in the 12-16 category was The Reluctant Journal of Henry K Larsen by Susin Nielsen, published by Andersen Press. In the 7-11 category the winner was The Journey written and illustrated by Francesca Sanna and published by Flying Eye Books. The winner for the 3-6 category was There’s a Bear on MY Chair by Ross Collins, published by Nosy Crow.

As the conference moves around, we are gradually infecting the UK with teachers hooked on reading quality books. The impact in their schools and upon the young people they teach has been positively awe inspiring. And of course books recommended by teachers are very popular with schools and parents. I strongly recommend authors to ensure their publishers are aware of the UKLA awards, which may be only 9-years-old but are growing in influence all the time.

Other Awards

There are many awards for children’s books in existence today and the Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook is probably the best source of information about them. Many are administered by the Booktrust so it is worth looking at their website and others are linked to children’s book writing festivals. Some awards require a submission fee from the publisher, so it can be very difficult for an individual author to influence this. It can be a marketing budget based decision.

In the feature, Joy recommended researching local awards in your area run by your local library service. Becoming well known in your local area – visiting schools and doing local bookshop signings is a good way to get your books noticed and considered for such awards. Once over the hurdle of submissions / nominations every award will have a different system of judging and / or voting, often by the children readers themselves.

The Coventry Inspiration Book Awards, which she created, has a tense system of Big Brother style voting. The book with the least number of votes is voted off each week until we get a winner. This ensures readers keep voting to keep their favourites in.

Anything which raises the profile of books and reading has to be a good thing. We all know that bookshops can have a bewildering array of titles and something having an award sticker can make a huge difference to sales. The most important thing about children’s book awards is the pursuit of excellence.

Joy Court can be found on Twitter: @Joyisreading

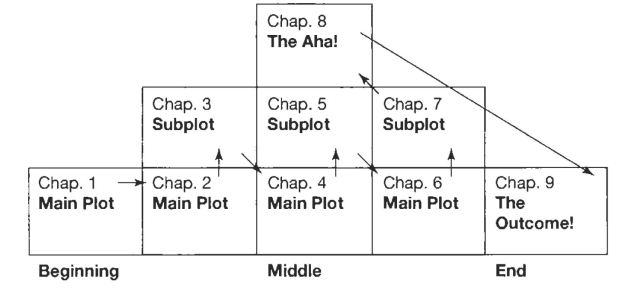

When the plan is in place and I am happy with it, I start to write the picture book. My recommendation to you if you are just starting out is to try and use this format. I hope you find it helpful. Of course if you use other methods of planning I would really be interested to find out more. Please let me know.

When the plan is in place and I am happy with it, I start to write the picture book. My recommendation to you if you are just starting out is to try and use this format. I hope you find it helpful. Of course if you use other methods of planning I would really be interested to find out more. Please let me know.