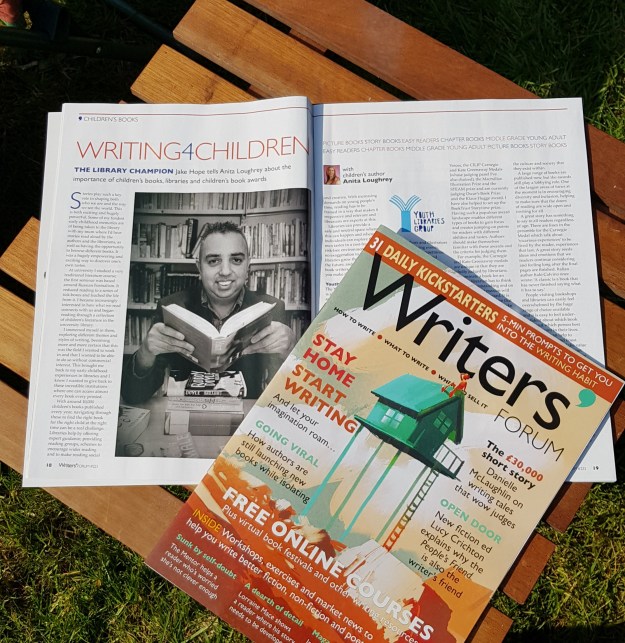

Jake Hope (Chair of CILIP’s Youth Libraries Group and Chair of the CILIP Carnegie and Kate Greenaway Awards Working Party) talked to me about the importance of children’s books, libraries and children’s book awards. He talked about how stories play such a key role in shaping both who we are and the way we see the world.

Some of his fondest early childhood memories are of being taken to the library with his mum where he would listen to stories read aloud during story times by the authors and the librarians, as well as having the opportunity to browse different books. He explained exploring and experimenting in this way is a hugely empowering and exciting way to discover and widen one’s own tastes.

Throughout his life Jake has immersed himself in exploring different themes and styles of writing. With around 10,000 children’s books commercially published every year, navigating through these to find the right book for the right child at the right time can be a real challenge. Libraries help by offering expert guidance, providing reading groups, schemes to encourage wider reading and to make reading social and creative. With increasing demands on young people’s time, reading has to be framed in a way that makes it responsive and relevant and librarians are experts at this.

Libraries can provide a safe and neutral space where this can happen and where individuals can explore their own tastes in a cost-free, risk-free environment. It is no exaggeration to say that libraries grow the readers of the future and as children’s book writers and illustrators you make this possible.

Youth Library Group

Jake told me that the Youth Libraries Group is all about connections. They are one of the special interest groups of CILIP (the library and information association) and have over 1,500 members. The membership is comprised of librarians working with children and young people in public libraries, in school libraries and for school library services – these are organisations who tailor collections of books to meet curriculum needs and who work to provide support and advice on reading for pleasure and library provision to schools.

The Youth Libraries Group is an extraordinary collective of highly committed and knowledgeable experts who share a unique passion for reading and for library provision for children and young people. The connections the group have means we are able to support through giving advice on what has been published in the past and present, providing access to groups of young readers who can often test manuscripts or provide insight into their reading tastes. They support authors and illustrators through organising events, promotions and competitions to bring greater focus and profile to creators.

Children’s book awards

Children’s book awards play a role in helping to make sure that certain types of book do not go unrecognised. Humorous writing, for example, does not always get the most recognition through awards, though funny books play such an important role in reading for pleasure. Awards like the Roald Dahl Funny Prize, as was, and the Laugh Out Loud awards, the LOLLIES, help to make sure these titles don’t get overlooked.

Jake has been a judge for many book awards such as: the Blue Peter Book Awards, the Costa, the Branford Boase, the Diverse Voices, the CILIP Carnegie and Kate Greenaway Medals (whose judging panel I’ve also chaired), the Macmillan Illustration Prize and the STEAM prize and am currently judging Oscar’s Book Prize and the Klaus Flugge award. He also helped to set up the BookTrust Storytime prize.

Having such a populous award landscape enables different types of books to gain focus and creates jumping-on points for readers with different abilities and tastes. Awards remain responsive to the culture and society that they exist within. Jake advises authors to make themselves familiar with these awards and the criteria for judging them.

“A large range of books are published now, but the awards still play a lobbying role. One of the largest areas of focus for this lobbying at the moment is in encouraging diversity and inclusion, helping to make sure that the doors of reading are wide open and are inviting for all.” Jake Hope

Jake elaborated that a great story has something to say to all readers regardless of age. Criteria are a useful way for book awards to appraise a range of different titles and styles of writing, but it’s important not to downplay the overall impact that language, characterisation, plot and style can have on a reader too.

“By working together and creating critical mass we can support one another and build new opportunities. With our combined skills and knowledge we can experiment and excite new generations of readers.” (Jake Hope)

People can easily feel overwhelmed by the huge range of choice that is available and it is easy to feel under-confident about which book might suit which person best at which point in their lives. Book awards can help to build awareness and boost confidence. In spite of the value of awards, it is important not to downplay the fact that every time a reader picks up a book and connects with it, this is the biggest win of all.

The present is not an easy time either for libraries or for authors and illustrators. Challenging times can present real opportunities for innovation and imagination, however, and by working together and creating critical mass we can support one another and build new opportunities. With our combined skills and knowledge we can experiment and excite new generations of readers.

To find out more about Jake Hope visit his website: www.jakehope.org and follow him on Twitter @jake_hope

To find out more about the Youth Libraries Group visit: www.cilip.org.uk/ylg and follow them on Twitter @youthlibraries

To read the complete feature you can purchase a copy of #223 2020 Writers’ Forum online from Select Magazines.

To read my latest Research Secrets or Writing 4 Children interviews you can invest in a subscription from the Writers’ Forum website or download Writers’ Forum to your iOS or Android device.